40 years of Hazelwood

The effects of a landmark case on free press

May 25, 2023

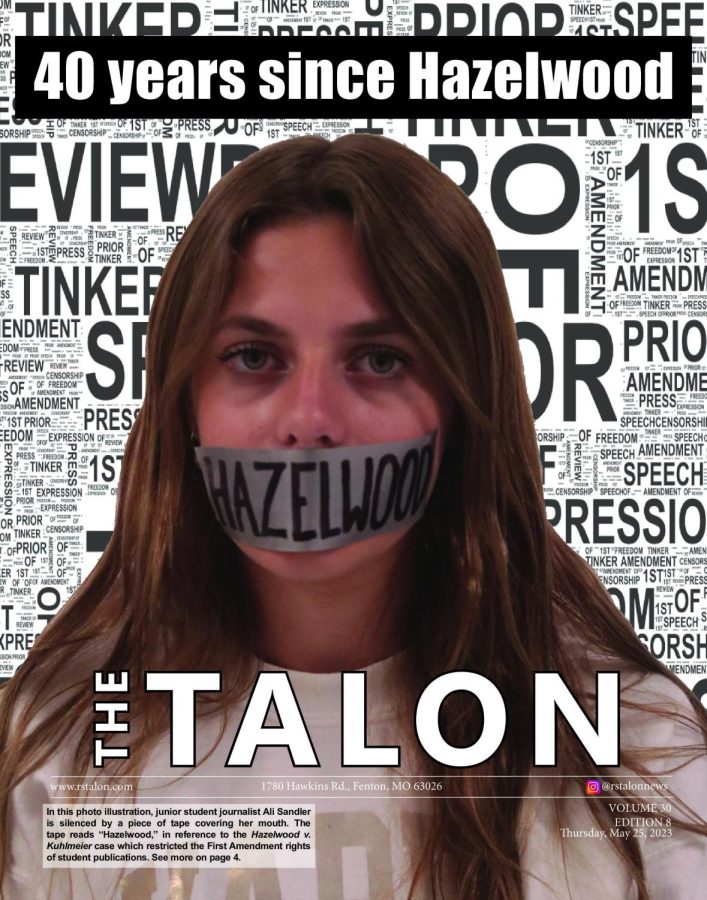

In this photo illustration, junior student journalist Ali Sandler is silenced by a piece of tape covering her mouth. The tape reads “Hazelwood,” in reference to the Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier case which restricted the First Amendment rights of student publications.

Teen pregnancy and divorce: 40 years ago, these topics left Hazelwood East High School torn. To the staff of the Spectrum, Hazelwood East’s school newspaper, the topics were applicable to the lives of students. To principal Robert Reynolds, though, the topics were inappropriate for a school environment. The Spectrum staff attempted to write stories concerning the subjects, along with teen marriage and runaways, in their edition that was published on May 13, 1983. However, Reynolds cut the pages from their paper without any forewarning.

Spectrum’s editors, including Cathy Kuhlmeier, partnered with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and took the district to court on the violation of the First Ammendment. Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, where a 5-3 decision ruled on the side of the Hazelwood School District.

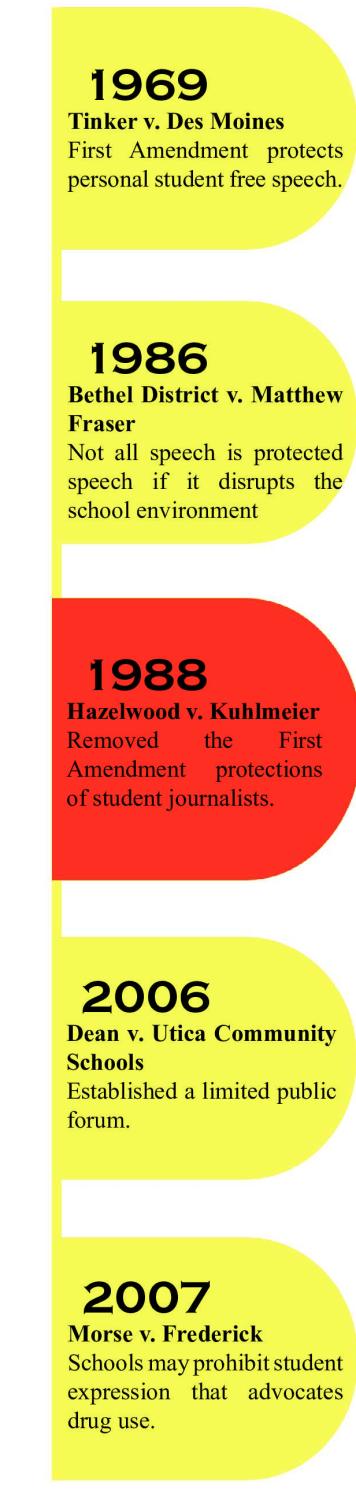

Previously, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals had sided with Kuhlmeier, citing the precedent set by Tinker v. Des Moines in 1969– students do not shed their constitutional rights on school grounds. However, Hazelwood established that schools have the ability to limit free speech within school sponsored activites if they are deemed innapropriate by the administration. The ruling removed First Ammendment protections for student run publications, even in public schools.

Since the case was decided on January 13, 1988, student journalists across the country have dealt with censorship. Just this March, the ACLU helped journalists at Northwest High School in Grand Island, Nebraska file a lawsuit against their school district after their school newspaper was shut down for covering LGBTQ+ topics. Hazelwood doesn’t just affect high school journalism, however. The decision also has a collegiate presence, with a survey from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression finding that 63.8% of student editors at public, four year universities had been censored during the 2020-2021 academic year.

Thirty-five years after the ruling, Kuhlmeier continues to fight for free press for students. She said she works with the New Voices movement, which has gotten laws passed in 17 states to counteract the impast of Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier.

“It’s still a relevant issue. Students are censored all the time. There is a movement across the nation called New Voices where we are working with state legislatures around the country to get new laws passed to essentially return the rights to student journalists. When we go into the state capitals we get students to give testimony about what is happening at the school level. It’s very moving to the legislators to hear students talk about their experiences,” Kuhlmeier said.

Currently, the Cronkite New Voices Act is pending in the Missouri Senate after being approved by the Missouri House of Representatives. However, this act would not largely affect the district, as the Rockwood Student Publications Policy already prohbits school administration from engaging in prior review of student publications. Principal Dr. Emily McCown agrees with the district policy since the publications are run by students, but said that the adviser had the responsibilty to make sure that all press coverage is impartial and factual.

“I think we stress that it’s a student-run publication, so they’re discussing stories about things that are important in student life, so it should be something that’s relevant to students. The only thing that I would talk to the newspaper adviser about is just making sure that articles are well rounded, and that we’re emphasising to our student journalists that both sides are presented and we’re not presenting a bias as student reporting. That’s really just more of a teaching moment, just to make sure that’s a part of the editing process and conversation,” McCown said.

The freedom of the press is still one of our rights. If we don’t stand up and defend it, and speak up about things that make a difference, are we going to continue to have any rights or will they all be pulled from us?

— Cathy Kuhlmeier

Government teacher MaryJo Bauer said that the case is a landmark, as it helps define relationships and legal rights for student reporters and keep student press educational, instead of just letting students have free reign and possibly disrupt the school environment.

“I think it helps clarify the line between the greater good of the entire student population and the desire to print a story. And I think it helps administrators find that line between censorship and free press,” Bauer said. “I think we’re supposed to be teaching students, I guess, not just opening the doors and saying free speech. Again, if you’re in an enviornment where the learning is disrupted, then it’s the greater will verus the individual right.”

However, senior Taylor Spencer, who was editor-in-chief of The Talon for the 2023-2023 school year, said that student publications are never trying to disrupt the school environment.

“Our intention is never bad. As journalists, we’re always trying to do our best. We’re not trying to create scandal or anything, we’re just trying to represent the school in an honest light,” Spencer said.

Should schools allow prior review?

Kuhlmeier said prior review from administration isn’t necessary when there is proper journalism education and trust in the adviser.

“It needs to start with your teachers, educating you on what your restrictions are [and] what good journalism consists of. How do you write good articles? What is newsworthy, and are you being accurate in it? And if you’re given those tools, you understand that then the only review needs to be coming from your adviser in a partnership with your staff. Your administration needs to trust the adviser to do their job, because it’s not the administration’s place to be in the middle of it,” Kuhlmeier said.

When it comes to controversial subjects, McCown said that she would rather be a part of the conversation to try and fix the issue rather than censor any discussion of it.

“I would probably just want some follow up conversations, because if it’s like a concern that’s going on that wasn’t on my radar then that’s something I would certainly want to talk about it. If there was a student who expressed an opinion, if that student was identifiable in the article, then maybe I would see if that was something I could follow up on. It would be more about how can I help a concern, if that’s what being presented, and be apart of the conversation,” McCown said